How Long Would You Live?

How Long Would You Live, If You Could Live Forever?

I’ve been asking this question to people for nearly a decade now (ever since I watched the Black Mirror episode “San Junipero.” If you haven’t seen it, it’s worth a watch—we’ll loop back to it at the end of this essay). For now I’ll just say that it’s fitting timing to write this since Season 7 of Black Mirror was released today. I have high hopes!

Anyway, I’ve asked this longevity question hundreds of times to a very wide range of people. It’s a fallback question I keep in my pocket for when there’s more time than topics. Even though I haven’t kept formal statistics, I’ve had the conversation enough to pull out themes and frequencies. Here’s how the conversation typically breaks down:

- Most people ask some clarifying questions

- They pick an age. Although I didn’t tell them this until later, there are only 6‑ish meaningfully different answers I’ve heard people give.

- We talk about their rationale and what I’ve gathered from others.

Clarifying questions

People usually want a little more info on the mechanism of the hypothetical. How’s their health? What’s the aging mechanism? I tell them they can have a choice:

- Proportional aging. If they want to live to be 1,000, they would spend ~60 years in their “60s.”

- Freeze at a single “perfect” age. For example, they could keep the health of a 25‑year‑old indefinitely, then very rapidly decline in their final years.

The second most common question is: “Do my loved ones also live the length I choose?”

I’ve always answered this with a:

“No, they live a normal human life span.”

It’s how I answered the first time I was asked, and I’ve just stuck with it. Writing this down, however, makes me want to explore how this severe penalty affects people’s answers.

These are by far the two most common clarifications. Other questions include how memories work, more details on sickness, whether other people know, etc.

Answers

The most common answer I get to this question is “I want to live a normal human lifespan.” Numerically, people tend to express this in the 80–100 yr range. Often, people who respond with this answer mention significant hesitations about outliving friends and family.

Nearly equal in frequency is “slightly longer than average,” which—if we take the numbers people use (100–120)—actually means something more like “in the top 1 %. of human lifespans” These people are comfortable with their lives and want to keep doing it a little longer than they expect to. But they usually seem wary of trying to imagine a qualitatively different human experience.

Next up is infinite. Some people—the wild ones—want to live forever. They want to have it all. Frankly, I suspect this is the worst possible answer, for reasons I’ll explain later.

Now we’re entering the uncommon territory. Even though this answer is less common than the previous two, living 2 × (160–200 years) the normal human lifespan is surprisingly common. People seem to answer this way when they’re thinking along the lines of “This life thing is pretty great. I’d do it again.”

The second‑rarest answer people routinely give is “in the 50s or 60s.” Some portion of people misunderstand the hypothetical and think they’d have to spend eternity in poor health. Even if I clarify the prompt, they double down on their original answer. But others—often people who have lived difficult lives—understand the prompt but want no more to do with life than is strictly required.

And finally, the least common answer I get is the “really long, non‑infinite time.” This is anywhere in the 1000 to 1,000,000 range.

Conclusion

It’s maybe obvious by now—or maybe it was obvious at the beginning—that a person’s answer to this question serves as a proxy for how much someone is enjoying their life. I’m simplifying, but there’s a strong correlation. The other (anti)-correlation I’ve noticed is that the older the person answering is, the shorter their answer is going to be. I don’t think I’ve ever asked this question to someone in their 60’s and had them say, “I wanna live for a billion years”. People seem to naturally find acceptance of death as they age.

Immortality

There’s also the matter of the people who want to live forever…

So many people talk about how “San Junipero” is their favorite episode of Black Mirror. It’s the one with the happy ending—the two lovers riding off into the virtual sunset to spend eternity with each other. The problem with this popular fairytale interpretation is that it neglects a thoughtful inclusion of the “Quagmire” scene. In the middle of the episode, the main character goes to a club called The Quagmire. The rave lit warehouse is filled with people having a seemingly fun (if extreme) time, but the conversational backdrop is quite explicit about the truth: The Quagmire is home to all of the system’s oldest residents. The ones who have already lived several normal human lifespans’ worth of experiences.

According to the conversation, there’s broad consensus that with each passing year, human brains must go to more extreme lengths to consider something novel, to feel alive and passionate, to have a reason and a purpose. When I see the pair of lovers drive off into the sunset in the final scene, I adopt the same conclusions as the Black Mirror writers: the lovers will eventually end up at The Quagmire, along with most or all of San Junipero’s residents.

And they’re equally doomed to stop going to The Quagmire one day.

Neither going to The Quagmire for the first time or leaving it for the last time are moral failings, they’re simply a side effect of humans propensities towards generalization while simultaneously craving novelty. As every drug user knows, “you only get your first time once”. But this tendency towards normalization applies to everything, not just drugs and other vices. I remember the first time I saw a Saguaro cactus. It was so cool that I stopped and took a picture of it. Now I could see hundreds in a day and not even register them.

One could argue that fizzling out, getting depressed, and eventually committing suicide is a small price to pay for immortality. I’m not so sure. Our biology simultaneously compels us toward self‑preservation just as strongly as it demands purpose.

The suicide quagmire might drag on for quite some time, but not forever…

Counter action

Again, we don’t have to be faced with possible immortality for these issues to be relevant. We all face this question of, “How do we keep our spark for life?”, or the equally cliche “How do you keep your sense of childlike wonder?” They’re cliches because they’re universal questions.

My answer is similar to the conclusion of John Salvatier’s blog post, Reality has a Surprising Amount of Detail:

This problem is not easy to fix, but it’s not impossible either. I’ve mostly fixed it for myself. The direction for improvement is clear: seek detail you would not normally notice about the world. When you go for a walk, notice the unexpected detail in a flower or what the seams in the road imply about how the road was built. When you talk to someone who is smart but just seems so wrong, figure out what details seem important to them and why. In your work, notice how that meeting actually wouldn’t have accomplished much if Sarah hadn’t pointed out that one thing. As you learn, notice which details actually change how you think.

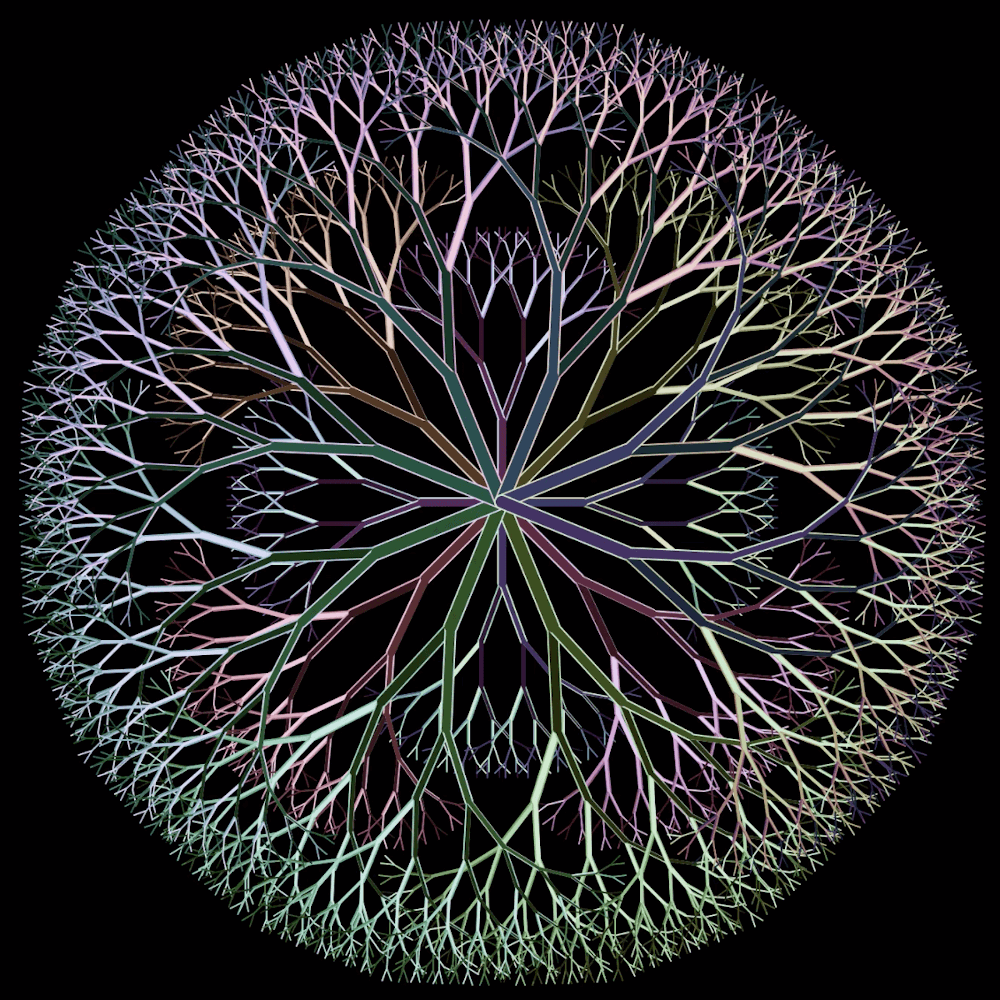

I’d like to add an addendum: as we age, try to look for and appreciate finer and finer grained detail. Reality is like a fractal: as you look closer and closer, you’ll notice more and more details that weren’t perceivable from a higher-level perspective.

The trick is realizing that the value of perception is scale invariant.

There’s no more inherent value in noticing a forest than there is a flower in that forest.